I have become, as followers of this blog hopefully realize, a person who cares about making as well as recognizing good arguments. It's a good skill to have because it helps to prevent one from being fooled. And, wow, this is a skill that has made me realize that people are out to fool others a lot! (On a side note, I think a lot of the people who try to fool others have been fooled themselves and are merely repeating the bad arguments that fooled them. It's not like they are intentionally out to fool. But I digress.)

One tactic I see used a lot is appealing to emotion. It is understandable why this is. When we get emotional, we can become irrational. So if you are out to fool someone, it is to your advantage to get your target into an irrational state. But, unfortunately, another flaw with us humans is that we are often not persuaded by reason alone. Emotion motivates us. So for people like me who want to make good arguments, this gets to be a bit of a bit of a conundrum.

The thought that I've had on this is that appeals to emotion can be acceptable as long as they are backed up with arguments that are good. But this is still a risky endevour. Even if I am being as honest as I can about my position, I may not be able to see flaws in my argument due to my own personal biases toward my position. For the sake of determining truth, it is good to be able to have others try to find such flaws. But if I've deliberately taken away that ability by making the emotional appeal...so much for that! Best way to put it is to say it is similar to a catch-22.

But, when action becomes necessary (as can be in the case of debating politics*), I am going to have to fall on the side of using emotion.

* That's a hint I'm working on some political posts that are going to evoke an emotional response.

Oh, look! While this was sitting in draft, I watched this The Daily Show clip that is rather relevant to the discussion.

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

IDHEF - Chapter 6, Addendum #5: Explaining gradual change through language.

This is part of my breakdown of the book "I Don't Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist." Related posts can be found by clicking here.

One example I really like to help explain the gradual change in organisms is the gradual change in language. Some example point out that languages such as Spanish, French, and Italian are all derivatives of Latin. But it's not like one day people were speaking Latin and then the next day they were speaking Spanish. No, it is a change that would have happened somewhat gradually.

Actually, take the English language of today, for example. There are essentially a couple* forms of English — British English and American English. Over in Britain, they spell some of their words differently. Like "theatre," "centre," "programme," or "tyre." Or, they will use different words than we do, like "flat" instead of "apartment." (Here is a link with a number of other examples.) I would imagine the transformation from Latin to Spanish would have been somewhat similar. Differences would have been more subtle at first, but would grow further and further apart with time.**

* I think Australia uses English similar to that in Britain, but it would not surprise me if they have some of their own unique differences as well. Heck, we have differences here amongst Americans. I.e, "pop" vs. "soda."

** On a somewhat related note, I suspect in older times where many people could neither read, write, nor communicate easily with those hundreds of miles away, changes could happen more quickly than they can today. Today, we can have local dialects, but those dialects can't really evolve into their own language because we have to be able to communicate with those from other dialects, so we need to keep the overall language mostly the same (and we have to be able to recognize where they differ). And we need to be able to understand documents written hundreds of years ago. In older times, this would not have been as true, so local dialects would essentially be the language and could change somewhat with each generation.

One example I really like to help explain the gradual change in organisms is the gradual change in language. Some example point out that languages such as Spanish, French, and Italian are all derivatives of Latin. But it's not like one day people were speaking Latin and then the next day they were speaking Spanish. No, it is a change that would have happened somewhat gradually.

Actually, take the English language of today, for example. There are essentially a couple* forms of English — British English and American English. Over in Britain, they spell some of their words differently. Like "theatre," "centre," "programme," or "tyre." Or, they will use different words than we do, like "flat" instead of "apartment." (Here is a link with a number of other examples.) I would imagine the transformation from Latin to Spanish would have been somewhat similar. Differences would have been more subtle at first, but would grow further and further apart with time.**

* I think Australia uses English similar to that in Britain, but it would not surprise me if they have some of their own unique differences as well. Heck, we have differences here amongst Americans. I.e, "pop" vs. "soda."

** On a somewhat related note, I suspect in older times where many people could neither read, write, nor communicate easily with those hundreds of miles away, changes could happen more quickly than they can today. Today, we can have local dialects, but those dialects can't really evolve into their own language because we have to be able to communicate with those from other dialects, so we need to keep the overall language mostly the same (and we have to be able to recognize where they differ). And we need to be able to understand documents written hundreds of years ago. In older times, this would not have been as true, so local dialects would essentially be the language and could change somewhat with each generation.

Monday, November 25, 2013

Failures of Agnosticism: Defining "God"

People who call themselves "agnostic" can** be really obnoxious. On thing that seems to be a common trend amongst such people is this point that we can neither prove nor disprove god and that arguments between theists and atheists are pointless. It is a reasonable sounding idea, but it has a huge problem of not defining the term "god." What these agnostics seem to mean when they use this term is a deistic form of god, which is one that created the universe, but otherwise does not interact with humans.

I have very few problems with such a god. In fact, I can agree with the agnostics' claim. The next problem, though, is that when people talk about "god," that's not the god they are talking about. When theists, for example, claim that homosexuality is an abomination as per their god, that's really not a deistic god that they describe.

Additionally, even claims about what could be a deistic god can fly in the face of known science. When theists claim that humans were created in their god's image, they could be talking about a deistic god — or, at least this is an action that could be compatible with such a definition. But we have evidence that this is not so and that humans evolved from ape-like ancestors. So I'm going to reject that god. I really don't care if I can't "disprove" it.

This is where the intellectual integrity of such an agnostic stance begins to break down. If the agnostic is going to tell me that I can't reject a god concept that flies in the face* of what is known about the world, then they are essentially advocating for relativism, which is "the concept that points of view have no absolute truth or validity, having only relative, subjective value according to differences in perception and consideration." In other words, it can be true for me that humans evolved and be true to some theists that humans were created. Or, likewise, true for me that homosexuality is not an abomination and be true to some theists that it is.

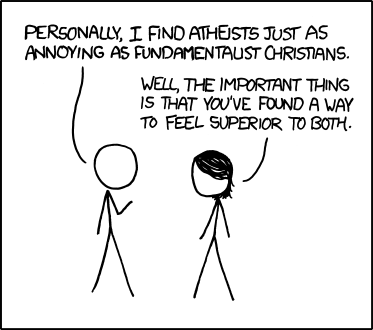

To be somewhat "fair" to the agnostics, I suspect that many of them really aren't relativists. It's probably more like what the classic XKCD comic suggests — they are trying to make themselves feel superior by trying to make themselves sound like they hold an intellectually superior position. This, though, is probably even worse than holding a relativist view. Because it's snobbish. And dishonest. I'll take an opponent who holds an intellectually bankrupt position any day over a dishonest snob who pretends to be intellectually superior.

UPDATE: Two things. One, I may be overstating my case. Slightly. These agnostics may not necessarily be relativists, but they may still be close enough. At the very least, they may not have a good understanding of how we do discover what is true. Or, perhaps they don't think the scientific method or other methods of empirical observation are good methods for finding truth. Still, this really doesn't make things better. Two, I should have said that if someone makes a claim about their god that flies in the face of what we know about the world, they had better present a lot of evidence to back up their claim! It could be that what we think we know is actually wrong.

* Alternatively, if they are going to tell me I can't reject such a god concept because I can't reject this generic universe-creating god concept, then that's just stupid. It's a different claim, despite the similarities it may have with the generic concept.

** Disclaimer: I hope it is clear that I'm not out to criticize all people who label themselves agnostics. I'm only out to criticize those who have the views as described.

I have very few problems with such a god. In fact, I can agree with the agnostics' claim. The next problem, though, is that when people talk about "god," that's not the god they are talking about. When theists, for example, claim that homosexuality is an abomination as per their god, that's really not a deistic god that they describe.

Additionally, even claims about what could be a deistic god can fly in the face of known science. When theists claim that humans were created in their god's image, they could be talking about a deistic god — or, at least this is an action that could be compatible with such a definition. But we have evidence that this is not so and that humans evolved from ape-like ancestors. So I'm going to reject that god. I really don't care if I can't "disprove" it.

This is where the intellectual integrity of such an agnostic stance begins to break down. If the agnostic is going to tell me that I can't reject a god concept that flies in the face* of what is known about the world, then they are essentially advocating for relativism, which is "the concept that points of view have no absolute truth or validity, having only relative, subjective value according to differences in perception and consideration." In other words, it can be true for me that humans evolved and be true to some theists that humans were created. Or, likewise, true for me that homosexuality is not an abomination and be true to some theists that it is.

To be somewhat "fair" to the agnostics, I suspect that many of them really aren't relativists. It's probably more like what the classic XKCD comic suggests — they are trying to make themselves feel superior by trying to make themselves sound like they hold an intellectually superior position. This, though, is probably even worse than holding a relativist view. Because it's snobbish. And dishonest. I'll take an opponent who holds an intellectually bankrupt position any day over a dishonest snob who pretends to be intellectually superior.

UPDATE: Two things. One, I may be overstating my case. Slightly. These agnostics may not necessarily be relativists, but they may still be close enough. At the very least, they may not have a good understanding of how we do discover what is true. Or, perhaps they don't think the scientific method or other methods of empirical observation are good methods for finding truth. Still, this really doesn't make things better. Two, I should have said that if someone makes a claim about their god that flies in the face of what we know about the world, they had better present a lot of evidence to back up their claim! It could be that what we think we know is actually wrong.

* Alternatively, if they are going to tell me I can't reject such a god concept because I can't reject this generic universe-creating god concept, then that's just stupid. It's a different claim, despite the similarities it may have with the generic concept.

** Disclaimer: I hope it is clear that I'm not out to criticize all people who label themselves agnostics. I'm only out to criticize those who have the views as described.

IDHEF - Chapter 6, Addendum #4: Yes, different words can create the same meaning.

This is part of my breakdown of the book "I Don't Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist." Related posts can be found by clicking here.

Back in part one of Chapter 6, the authors thought they'd present the speculation that just one change in a letter could produce an entirely different meaning. Even though there really is no need to entertain pure speculation since speculation alone tells us nothing about what it true, I did ofter a counter-argument that multiple changes can result in virtually no difference in meaning. (My examples were the change from "god" to "deity" and "dog" to "canine".) Well, I've been listening to interviews of Marlene Zuk, author of the book, Paleofantasy: What Evolution Really Tells Us about Sex, Diet, and How We Live. In this book, she talks about how multiple groups of humans that raised cattle gained a tolerance to lactose. Additionally, the genes that produced the tolerance are different per for each locale that developed each tolerance. In other words, it was essentially a different combination of letters producing the same result. If this is true, then it would appear that my counter-argument actually has evidence to back it up.

Now, to be fully honest, I do suspect that there is truth to what the authors claim about one change in a letter potentially generating a difference in "meaning." However, there is no reason to believe that would be some point that cripples the theory of evolution. (And with examples such as the above, it would seem that the evidence shows that it does not cripple the theory.) Indeed, evolutionary theory actually accounts for such changes. With evolution, changes that produce a different "meaning" that are disadvantageous get "weeded out" as the organism with the change will then be less likely to reproduce and pass on the change to offspring.

This also furthers my point back in part one where I stated, "It is simply not true that comparing cell information to encyclopedias is a one-to-one relationship." At that point, I mentioned about how encyclopedias will tend to be bigger as time progresses as there will be more information to include. One other consideration that was not made is that there can be multiple ways to assemble an encyclopedia. There is not just one encyclopedia. Britannica makes encyclopedias, but so does World Book. Then, there is my favorite: Wikipedia (which I often link in posts as a reference). So there are multiple ways in which to configure an encyclopedia and still have a valid encyclopedia. Likewise, it would seem there can be many ways in which to "configure" an organism and still have a functional organism.

Back in part one of Chapter 6, the authors thought they'd present the speculation that just one change in a letter could produce an entirely different meaning. Even though there really is no need to entertain pure speculation since speculation alone tells us nothing about what it true, I did ofter a counter-argument that multiple changes can result in virtually no difference in meaning. (My examples were the change from "god" to "deity" and "dog" to "canine".) Well, I've been listening to interviews of Marlene Zuk, author of the book, Paleofantasy: What Evolution Really Tells Us about Sex, Diet, and How We Live. In this book, she talks about how multiple groups of humans that raised cattle gained a tolerance to lactose. Additionally, the genes that produced the tolerance are different per for each locale that developed each tolerance. In other words, it was essentially a different combination of letters producing the same result. If this is true, then it would appear that my counter-argument actually has evidence to back it up.

Now, to be fully honest, I do suspect that there is truth to what the authors claim about one change in a letter potentially generating a difference in "meaning." However, there is no reason to believe that would be some point that cripples the theory of evolution. (And with examples such as the above, it would seem that the evidence shows that it does not cripple the theory.) Indeed, evolutionary theory actually accounts for such changes. With evolution, changes that produce a different "meaning" that are disadvantageous get "weeded out" as the organism with the change will then be less likely to reproduce and pass on the change to offspring.

This also furthers my point back in part one where I stated, "It is simply not true that comparing cell information to encyclopedias is a one-to-one relationship." At that point, I mentioned about how encyclopedias will tend to be bigger as time progresses as there will be more information to include. One other consideration that was not made is that there can be multiple ways to assemble an encyclopedia. There is not just one encyclopedia. Britannica makes encyclopedias, but so does World Book. Then, there is my favorite: Wikipedia (which I often link in posts as a reference). So there are multiple ways in which to configure an encyclopedia and still have a valid encyclopedia. Likewise, it would seem there can be many ways in which to "configure" an organism and still have a functional organism.

Sunday, November 24, 2013

IDHEF - Chapter 6, Addendum #3: Teaspoon Fossils

This is part of my breakdown of the book "I Don't Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist." Related posts can be found by clicking here.

While I was writing my initial responses to Chapter 6, the authors' remarks on fossils and molecular isolation had really been bothering me as I wasn't sure how best to address it. I ended up quoting another blogger, but I think I've finally come up with how I want to address this topic.

One of the things I have come to realize, which I should have picked up on more before, was that these authors overlooked the part about how where fossils are discovered is very much important to the evidence that the fossil record provides. The authors portrayed fossil evidence as merely lining up fossils to show progression, using the analogy of a teaspoon evolving into a pot to demonstrate the absurdity of this idea. I had mocked one gaping flaw in the analogy in that it ignores reproduction as a very important component to evolutionary theory. This is certainly a big flaw, but not the only flaw. For reference, here is the picture they use:

The other flaw is that the authors make the fossil record sound like scientists aligning similar fossils in a line based on the progression of the features. (This is how the authors line up their counter-example of a teaspoon progressing into a pot.) This is not correct; the fossils are going to be aligned based on the age of the fossils. Signs of progression is the result of such alignment and these signs of progression are evidence for evolution.

For reference, the book reads as follows:

Going to the authors' teaspoon example (and ignoring for the sake of argument the fact that teaspoons can't reproduce), if the pot (or large kettle) were to have evolved from a teaspoon, we would expect to find pots in a geological layer of rocks younger than those in which we find teaspoons. If not, then when would lack evidence that evolution occurred as we would fail to see a progression when lining up the fossils by age. It's nearly that simple.

There are a few caveats, though. We could, for example, find pots and teaspoons in the same rock and this would not necessarily be a disproof of evolution. For one, we need to realize that teaspoons don't necessarily disappear just because some set eventually evolved into a pot. There is this cliche question in creationist circles that asks, "If we evolved from monkeys, then why are there still monkeys?" My favorite response to this is to ask the question, "If America was colonized by the British, why are there still British?" The answer here is fairly simple — Some of the British stayed in Britain! Likewise, some monkeys essentially stayed monkeys. Or some teaspoons may have stayed teaspoons.

Additionally, finding a pot in the fossil record earlier than teaspoons would not necessarily be a disproof of evolution. It could be that we just haven't found the earlier teaspoon fossils or maybe no teaspoons fossilized and there may be none to find. So a lack of fossils doesn't mean it didn't happen. The case for evolution is indeed weaker without such fossils, but that's the worst that can be said.

I also need to speak more about how the fossil record is more like supporting evidence than evidence in itself, like I did near the end of Part I. I gave an example there, but what I would really like to do is also use the authors' own example. For this, we need to turn back to Chapter 3. In this chapter, the authors talk about radiation from the big bang (pages 81-82). They state that "scientists predicted that this radiation would be out there if the Big Bang did really occur" (p 81). Here's my question: Without other supporting evidence for the big bang, would this radiation alone be enough to support the big bang theory? I suspect not. After all, this is just one out of five points in what the authors refer to as SURGE. So when the authors treat the fossil record as though it alone can prove evolution, they're being disingenuous. Fossils are to evolution much the same way background radiation is to the big bang — both are used to support predictions made by the respective theories, but neither alone proves them. If I know my history as well as I think I do, it was predicted even by Charles Darwin that, if enough fossils could be found, those fossils would show a progression over time. They have, thus they validate this prediction. But you most likely would not be able to look at fossils and work out the theory of evolution from those fossils. Likewise, I doubt someone could look at background radiation and work out the big bang theory. It doesn't work that way and it's not supposed to work that way. Arguing that you can't derive evolution from fossils is then not a valid argument.

While I was writing my initial responses to Chapter 6, the authors' remarks on fossils and molecular isolation had really been bothering me as I wasn't sure how best to address it. I ended up quoting another blogger, but I think I've finally come up with how I want to address this topic.

One of the things I have come to realize, which I should have picked up on more before, was that these authors overlooked the part about how where fossils are discovered is very much important to the evidence that the fossil record provides. The authors portrayed fossil evidence as merely lining up fossils to show progression, using the analogy of a teaspoon evolving into a pot to demonstrate the absurdity of this idea. I had mocked one gaping flaw in the analogy in that it ignores reproduction as a very important component to evolutionary theory. This is certainly a big flaw, but not the only flaw. For reference, here is the picture they use:

The other flaw is that the authors make the fossil record sound like scientists aligning similar fossils in a line based on the progression of the features. (This is how the authors line up their counter-example of a teaspoon progressing into a pot.) This is not correct; the fossils are going to be aligned based on the age of the fossils. Signs of progression is the result of such alignment and these signs of progression are evidence for evolution.

For reference, the book reads as follows:

Gee, how can you ignore the fossils? The skulls look like they're in a progression. They look as if they could be ancestrally related. Is this good evidence for Darwinism? No, it's not any better than the evidence that the large kettle evolved from the teaspoon. (p153)

Going to the authors' teaspoon example (and ignoring for the sake of argument the fact that teaspoons can't reproduce), if the pot (or large kettle) were to have evolved from a teaspoon, we would expect to find pots in a geological layer of rocks younger than those in which we find teaspoons. If not, then when would lack evidence that evolution occurred as we would fail to see a progression when lining up the fossils by age. It's nearly that simple.

There are a few caveats, though. We could, for example, find pots and teaspoons in the same rock and this would not necessarily be a disproof of evolution. For one, we need to realize that teaspoons don't necessarily disappear just because some set eventually evolved into a pot. There is this cliche question in creationist circles that asks, "If we evolved from monkeys, then why are there still monkeys?" My favorite response to this is to ask the question, "If America was colonized by the British, why are there still British?" The answer here is fairly simple — Some of the British stayed in Britain! Likewise, some monkeys essentially stayed monkeys. Or some teaspoons may have stayed teaspoons.

Additionally, finding a pot in the fossil record earlier than teaspoons would not necessarily be a disproof of evolution. It could be that we just haven't found the earlier teaspoon fossils or maybe no teaspoons fossilized and there may be none to find. So a lack of fossils doesn't mean it didn't happen. The case for evolution is indeed weaker without such fossils, but that's the worst that can be said.

I also need to speak more about how the fossil record is more like supporting evidence than evidence in itself, like I did near the end of Part I. I gave an example there, but what I would really like to do is also use the authors' own example. For this, we need to turn back to Chapter 3. In this chapter, the authors talk about radiation from the big bang (pages 81-82). They state that "scientists predicted that this radiation would be out there if the Big Bang did really occur" (p 81). Here's my question: Without other supporting evidence for the big bang, would this radiation alone be enough to support the big bang theory? I suspect not. After all, this is just one out of five points in what the authors refer to as SURGE. So when the authors treat the fossil record as though it alone can prove evolution, they're being disingenuous. Fossils are to evolution much the same way background radiation is to the big bang — both are used to support predictions made by the respective theories, but neither alone proves them. If I know my history as well as I think I do, it was predicted even by Charles Darwin that, if enough fossils could be found, those fossils would show a progression over time. They have, thus they validate this prediction. But you most likely would not be able to look at fossils and work out the theory of evolution from those fossils. Likewise, I doubt someone could look at background radiation and work out the big bang theory. It doesn't work that way and it's not supposed to work that way. Arguing that you can't derive evolution from fossils is then not a valid argument.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)